The

Messiah and the Davidic Covenant

The Davidic Covenant promised:

1.

An

eternal house (this refers to the dynasty of David; the house of David or the

line of David).

2.

An

eternal throne (this refers to a permanent right to reign that was to be held

by the house of David).

3.

An

eternal kingdom (Israel

4.

An

eternal descendent (necessary if the house, throne and kingdom are to last

forever).

That the Davidic Covenant climaxes

in the person of the Messiah is supported by Scripture. Peter references it in

his address at Pentecost. “Men and brethren, let me speak freely to you of the

patriarch David, that he is both dead and buried, and his tomb is with us to

this day. Therefore, being a prophet, and knowing that God had sworn with an

oath to him that of the fruit of his body, according to the flesh, He would

raise up the Christ to sit on his throne, he, foreseeing this, spoke concerning

the resurrection of the Christ, that His soul was not left in Hades, nor did

His flesh see corruption.” (Acts 2:29-31) Here is the eternal One,

resurrected to sit eternally on the Davidic throne.

In this address Peter draws on Psalm

16 to demonstrate that the resurrection of Jesus was predicted, and since the

Psalm was Davidic it must mean that this One who has been resurrected, the

Messiah of Israel, must also be the One to inherit the throne of David and

reign eternally. Peter builds his case quickly and well. Since he was speaking

on the anniversary of the death of David, and because the tomb of David was

known to his hearers, he confidently asserted that Israel

A later episode is described in Acts

15. There Luke undertakes to report on the debate in Jerusalem

Not only ‘Son of David’ but also ‘King of the Jews’

It was crucial to the Messianic

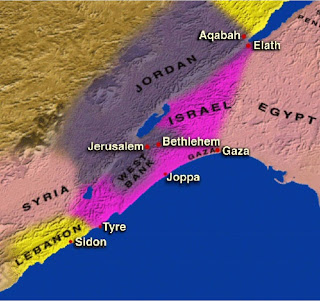

claim of Jesus that he should have been born in David’s town of Bethlehem

At the centre of the rejection of

Jesus as Messiah was the reluctance of the Sanhedrin to acknowledge this aspect

of the claim of Jesus. When He entered Jerusalem riding on a donkey,

deliberately fulfilling the Zechariah prophecy, “Tell the daughter of Zion,

‘Behold, your King is coming to you, Lowly, and sitting on a donkey, A

colt, the foal of a donkey,’” (Matt.

21:4-5) they complained of the crowd’s reaction when they praised the Son of

David. This public display of power and popularity undoubtedly hardened their

opposition and resistance. Their actions the following week where they sought

opportunity to bring a political accusation against Him were partly a reaction

to this event.

That Jesus had title to the Davidic

throne is clear, but the time when His reign would begin is less clear. The

disciples had thought it was imminent. After the resurrection and before the

ascension they asked the risen Messiah, “Lord,

will You at this time restore the kingdom to Israel Israel Jerusalem Jerusalem